How This Man Made $60K in 2 Months as an Independent Claims Adjuster

As August turned into September in 2017, the eyes of the nation were glued to their tablets, phones and TV screens. Hurricane Harvey had just slammed Texas with record rainfall and catastrophic flooding, and Hurricane Irma was tearing through the Caribbean with its sights set on Florida.

It seemed like The Weather Channel was on wherever you went.

Brett Brown’s eyes were fixed on his computer screen too, but for different reasons: He was hunting for a job.

Fresh out of grad school with a degree in plant pathology, Brown was back in his hometown of Mobile, Alabama, and looking to put his education to good use. But as we all know, landing a job is easier said than done.

So when Brown got a phone call from an old family friend about a temporary job opportunity, he was intrigued. Would he be willing to do some work in Florida for a few weeks after Irma passed? The friend told Brown that he could make enough to pay off most of his student loans, if not all of them.

Naturally, Brown was skeptical. Usually when you get a call out of the blue about a job that pays thousands of dollars and requires no previous experience, it’s too good to be true. But for independent insurance adjusters in the aftermath of a natural disaster, those kind of earnings are very real.

So Brown loaded up his truck and headed to Florida.

Becoming an Independent Catastrophe Claims Adjuster

Independent adjusters work as a contractor for an adjusting firm. Earnings vary, depending on the amount of work put in and the adjusting firm’s fee schedule, but skilled independent adjusters can make upwards of six figures a year.

Like staff adjusters, who work for one company, or public adjusters, who represent policy holders, independents can handle daily claims, catastrophe claims or a mix of both. Daily work consists of routine claims that happen all the time, like water damage from a busted pipe. Catastrophe claims are the result of a natural or man-made disasters, such as a hurricane or an oil spill.

Brown hadn’t abandoned his goal of working in horticulture, but when an opportunity to make good money comes a-knockin’ (or, in this case, calling) he took it.

Adjusters Needed — Badly

Because Harvey and Irma happened in such quick succession, Florida faced a monumental problem: a shortage of insurance adjusters. Staff and independent adjusters from all over the country had already made their way to Texas by the time Irma barreled through the Sunshine State.

With two of the country’s largest and most populated states hit hard by hurricanes that caused over $290 billion in damages, independent catastrophe adjusters were in high demand, and firms were willing to take on people with little to no experience.

So on Sept. 12, 2017, Brown found himself at the Quality Inn & Suites in Gulf Breeze, Florida, to start training as an independent claims adjuster for the Canada-based company Catastrophe Response Unit. He had zero experience and wasn’t quite sure what he’d had signed up for.

The Training Process

Brown and about 70 other people in his group spent the next five days filling out paperwork, watching training videos, taking tests and listening to presentations on proper procedures for inspecting and processing claims. Since the need for adjusters was so high, the training process was streamlined.

“They were just trying to get people out in the field and get clients seen and properties inspected as soon as they possibly could,” Brown says.

He had to learn the industry’s standard software for property claims estimation. And he had to buy it — for $150. Independent claims adjusters cover their expenses — lodging, gas, food, the whole nine yards — out of pocket. Fortunately for Brown, he already had a laptop, a ladder and a truck.

“[Catastrophe Response Unit] stressed that you don’t think about the money that you’re spending now,” Brown says. “Just think about the investment that you’re making for yourself in the next month or two.”

Claims adjusters, even temporary ones, must be licensed, and each state has its own rules and regulations. After completing the five days of training and certification, Brown earned an emergency license. Several states — Florida being one of them — make these available during catastrophe situations.

How Payment Is Made

Independent adjusters work on a contract basis, with their pay based on a fee schedule rather than a salary or hourly wage. An insurance company pays the independent adjusting firm a certain fee per every claim closed; the percentage paid is based on the final claim settlement. Once the company receives its fee, it pays the adjuster a portion, which generally ranges from 55% to 70%. (With CRU, Brown’s was around 60%.)

To break it down a little further: When Brown processed a claim of up to $20,000, he made $600. For claims between $20,000 and $50,000, he took home $900; over $50,000, his fee was $1,200.

In other words, the more difficult and costly the claim, the higher the payout.

A Day in the Life

After completing the speedy training process, Brown headed south to set up base in Tampa, Florida. With no previous experience in claims adjusting, the learning curve was steep. His first week was pretty rough.

Brown started with 50 claims. He had to contact each policyholder to schedule a time to view the damage before he could get out in the field. He booked visits to homes near one another in order to maximize the amount of visits he could make in a day.

Once he had some inspections scheduled, the hard, physical work really kicked in.

Brown set his alarm for 6 a.m., with his first inspection starting as early as 7:30. Although he was based in Tampa, his appointments took him all over central Florida.

Inspections averaged about an hour, depending on the amount of damage. While he only took on one or two inspections a day in the beginning, Brown added more as he grew comfortable. By his second week, he was logging four or five claims a day. At his busiest times, Brown handled up to 10 in a single day.

Once he found his groove, he was earning between $600 and $6,000 a day.

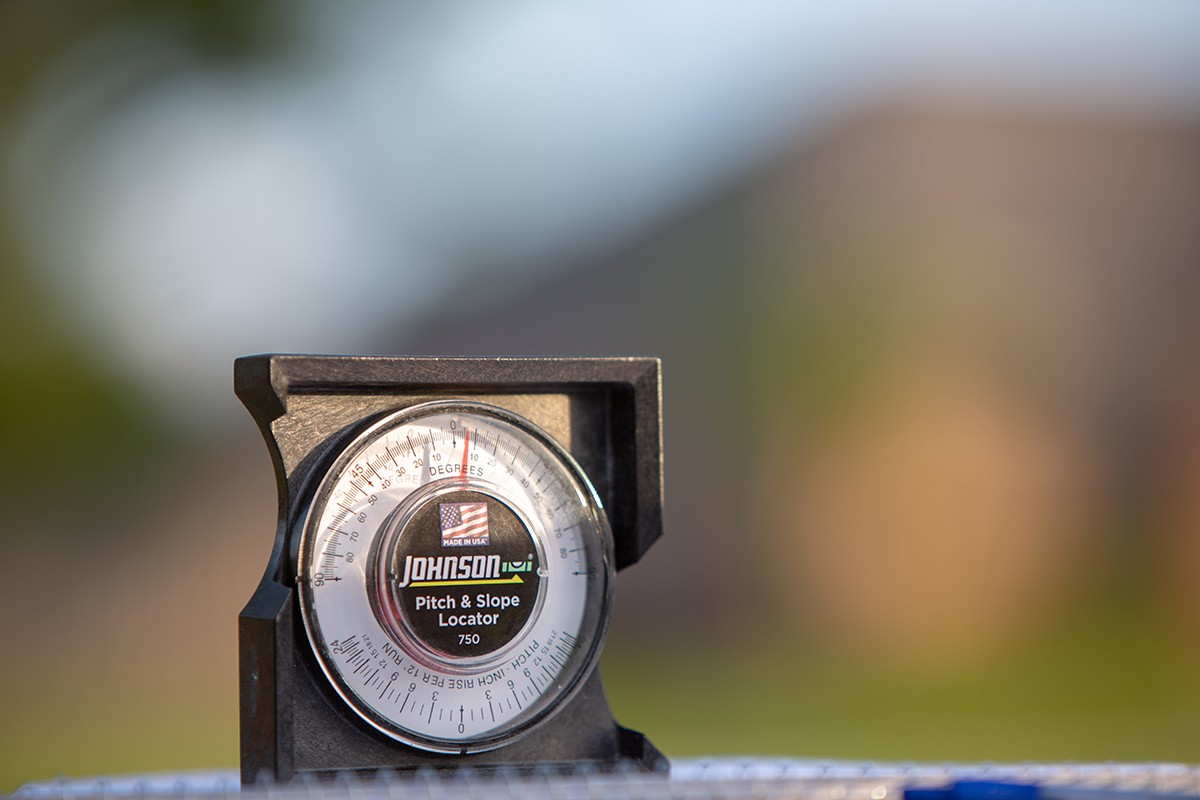

Whether the property was missing a few shingles or had lost an entire wall, each one required extensive inspection. Hauling around a ladder and climbing up on roofs was part of the job — and don’t forget this was all in Florida, where autumn is an urban legend and 90-degree days are standard.

It was on one of those roofs, about a week in, that Brown realized his worn-out New Balances were not proper footwear. He found himself trapped on a particularly steep roof, in danger of sliding off. Brown avoided his own catastrophe, but invested in some sturdy, non-slip work boots.

After a long day of inspections, with maybe a 30-minute lunch break squeezed in, Brown would head back to the rental house he shared with other CRU adjusters he met during training. But his work was far from over. In order to get the claim processed, paperwork for each inspection was required. He’d stay up until about midnight entering damages into his software and drawing up paperwork, then set his alarm and wake up at 6 to do it all over again.

Brown’s insanely long hours are an industry norm during a catastrophe. “They stay in a fleabag hotel and work 16 hours a day, six to seven days a week,” says Peter Crosa, who owns Peter J. Crosa & Co. and has been in the adjusting business for over 40 years. “They end up making a lot of money… but it’s tough duty.”

In addition to being away from home, driving to properties scattered across several counties and working 16-hour days, Brown had to meet with people who were dealing with the nightmare of a damaged or destroyed home. That part was challenging and emotionally draining.

In all, though, Brown found the job quite rewarding. He was, after all, helping people in times of dire need.

The Net Result

On Nov. 1, Brown packed his bags and headed home to Alabama. Less than two months of working 16-hour days, seven days a week had grossed him over $60,000.

After deducting taxes, which as an independent contractor he had to handle on his own, Brown netted about $40,000. He decided to put a little bit away for rainy days and investments. The rest went toward his student loans, and he was able to pay off the majority. Brown still has some debt left, but imagine the relief of paying off $40,000 worth of loans in one sitting.

So was it all worth it?

“Oh, absolutely,” Brown says. “The first couple of weeks, I was doubting myself and the opportunity as a whole, but after that second week it really became clear that this was not just blowing smoke.”

Brown still plans to pursue a career in horticulture. But he says he won’t totally rule out doing some short-term claims adjusting in the future — especially now that he knows what he’d be getting himself into.

After all, he’s still got more student loans to pay.

Kaitlyn Blount is a junior staff writer at The Penny Hoarder.